- Introduction

- What are Linters and Formatters

- What is Ruff?

- Getting Started with Ruff

- Tips

- Conclusion

- Further Reading

Introduction

Python development is evolving—today, code quality and consistency are more important than ever. Strict is the new cool.

Tools like Black have made opinionated formatting mainstream, and the need for readable, maintainable, and error-free code is greater than ever—especially as projects grow and AI-driven code/tools become more prevalent.

As The Zen of Python reminds us, “Readability counts”. The developer principle “code is written once but read many times” is still widely cited. But, maintaining high standards manually can be challenging and time-consuming. That’s where modern linters and formatters come in, helping us catch errors early and keep our codebases clean.

In this post, I’ll share my experience adopting Ruff, a fast, modern linter and formatter.

What are Linters and Formatters

Linters

Linting is the automatic checking of your code for errors. Code that passes linting will probably run.

Technically, linting is Static Analysis, meaning they detect defects without running the code by analysing the syntax. Modern linters will also check for improvements to the code that may lead to incorrect results: suggesting more robust or accepted ways to code.

Linters reduce errors and improve the quality of your code and therefore should be enabled in IDEs, where they continuously run in the background. Any CI/CD pipeline or pre-commit process should have linting enabled.

A linter can be thought of as a formatter with syntax rules.

Formatters

A formatter makes your code pretty by standardising the appearance of the code. Formatters only change the presentation of the code, not its functionality.

This makes the code easy to read for you and everyone else, and this becomes more important when working in teams.

Formatters use a set of rules for consistency. The PEP 8 – Style Guide for Python Code is one such set of standardised rules, but there are numerous anti-pattern rules followed by different formatter implementations as well.

A formatter is opinionated about what it thinks pretty code is, but usually those opinions can be enabled, disabled, or ignored.

Why You Should Use Them

What is Ruff?

Ruff is a fast, modern Python combined linter and formatter from Astral, the company that developed UV (see My Switch to UV).

Key features of Ruff:

- Written in Rust, so it’s fast

- A linter and formatter in one tool

- Designed as a compatible replacement for multiple existing linters and formatters

- Configurable (enable/disable) rules for linting and formatting

- IDE integration

- Command Line (CLI) usable

- Works for Python >=3.7

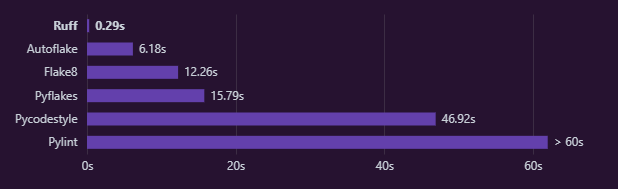

So Ruff simplifies multiple linters and formatters into a single tool and performs those tasks fast. How quickly?

This graph from the Ruff website shows the time taken to lint the entire CPython codebase:

source: https://docs.astral.sh/ruff

source: https://docs.astral.sh/ruff

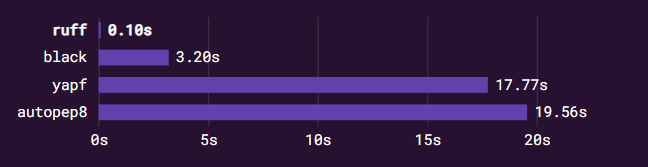

Taken from an Astral blog post, this graph shows the timings to format the ~250k line Zulip codebase:

source: https://astral.sh/blog/the-ruff-formatter

source: https://astral.sh/blog/the-ruff-formatter

Some of the tools it replaces are:

-

flake8 (plus dozens of plugins)

Getting Started with Ruff

Installation steps

Being an Astral tool, there are multiple methods of installing Ruff.

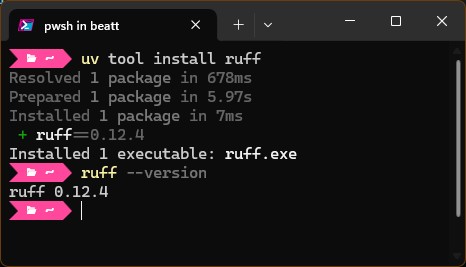

For me, I want to install Ruff as a system tool, so it is globally available to me all the time. I have UV installed, so I will install using that:

uv tool install ruff

If you do not have UV installed (I recommend you do; see My Switch to UV), you can install it directly with PowerShell:

powershell -c "irm https://astral.sh/ruff/install.ps1 | iex"

Alternatively, you can add it to your project tools as part of your virtual environment, or use other, more traditional, installation methods, e.g., pip, pipx:

uv add --dev ruff # Install into Project Development Environment

pip install ruff # Use one of the older install methods

See the Ruff Install Documentation if your preferred install method is not mentioned here.

Basic CLI Usage

Once installed, you can run Ruff on the command line:

ruff check # Recursively lints all files, from this working directory

ruff check . # Recursively lints all files, from this working directory

ruff check test.py # Lint specific file only

ruff check *.py # Lint all Python files in the current directory

ruff format # Recursively format all files, from this working directory

ruff format . # Recursively format all files, from this working directory

ruff format test.py # Format specific file only

ruff format *.py # Format all Python files in the current directory

If you have not installed Ruff, but want to run the tool from within a UV-cached environment via UVX:

# uvx is an alias for uv tool run

uvx ruff check # Recursively lint all files, from this working directory

uvx ruff format # Recursively format all files, from this working directory

That’s all there is to it: two simple commands to lint and format.

The results of running either command are the important thing. As an example, let’s take this highly contrived, simple Python file that has syntax errors and formatting issues:

1from sys import *

2import os, math

3

4num_strs = {"Zero": 0,"One":1, "Two": 2 , "Three": 3}

5str_nums = {0: "Zero" ,1:"One", 2:"Two" , 3: "Three"}

6

7def TranslateNumberString(numberstring

8):

9

10 """

11 Example function

12 """

13 if (True,):

14 return num_strs[numberstring]

15

16from pprint import pprint

17

18if __name__ == "__main__":

19 pprint(num_strs)

20 pprint(str_nums)

21 for x in range(3):

22 try:

23 r = TranslateNumberString(str_nums[x])

24 print('Str {} = {}'.format(str_nums[x], r))

25 except:

26 print("Damn!")

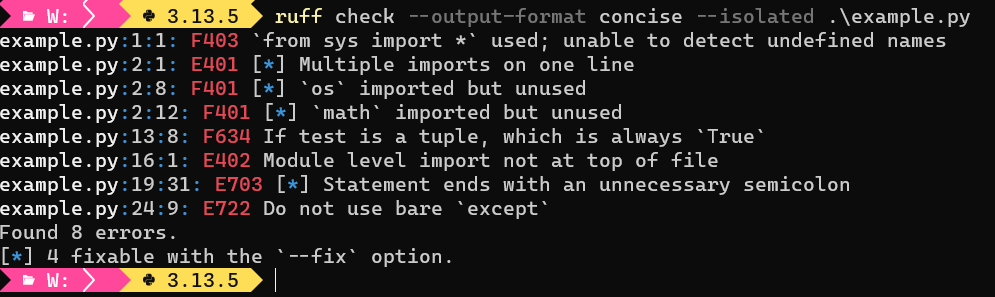

ruff check --output-format concise .\example.py

Here, I am linting this file and nd have set the output to concise (default is full), and passed in the --isolated flag (so Ruff will ignore my config files and use the defaults instead), see Configuration.

I did say this was contrived!

Even from those few lines of rushed code, I’ve got eight syntax errors.

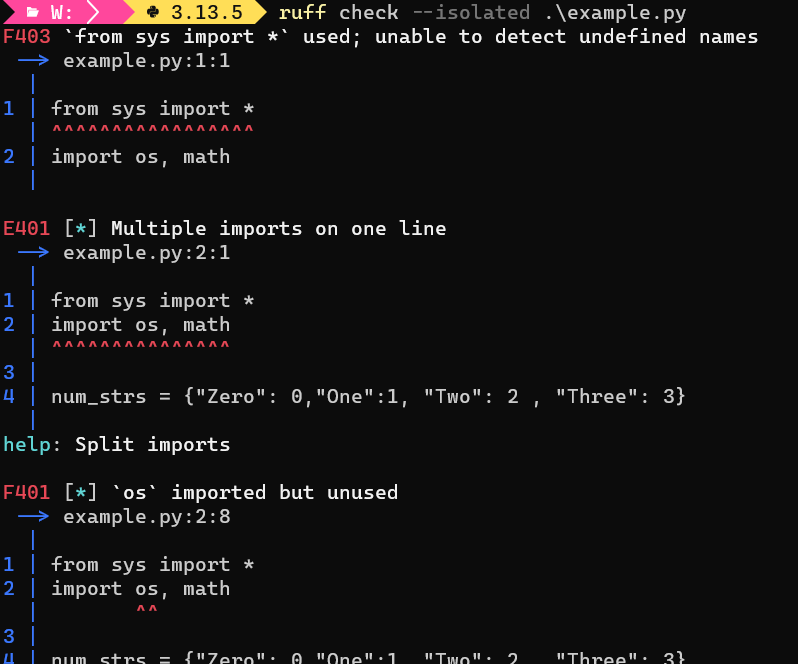

The full format explains each fault found in more detail, for example:

ruff check .\example.py

# Both lines are equivalent

ruff check example.py

ruff check --output-format full example.py

The linter cannot always fix detected issues. For the rules the linter can fix, see the legend in the Ruff Rules Documentation.

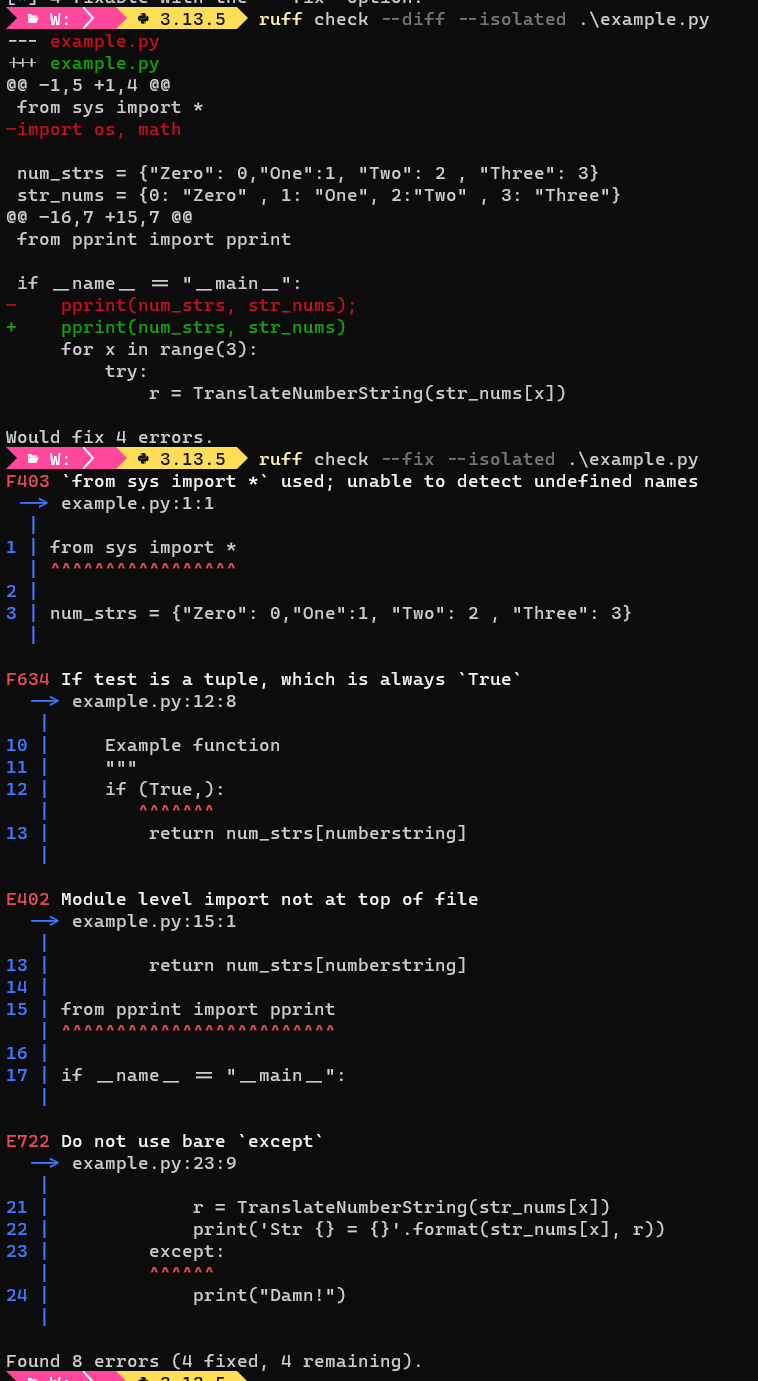

In this example, there are four errors fixable automatically (those with [*]). Let’s’ fix the easy ones automatically, as they are simple errors:

ruff check --diff example.py # Show what the changes 'would' be

ruff check --fix example.py # Apply the changes

You may get fixes that Ruff has classified as unsafe, indicating that the meaning of your code may change with those fixes. There are none in the example, but the commands to fix the unsafe-fixes are similar:

ruff check --unsafe-fixes --diff example.py # Show what the changes 'would' be

ruff check --unsafe-fixes --fix example.py # Apply the changes

Now we are down to four errors for our example, but there are no automatic fixes for those. Let’s go read the documentation for each errored rule and fix them manually:

- F403

from sys import *used; unable to detect undefined names- Yes, star imports are bad, change to

import sys

- Yes, star imports are bad, change to

- F634 If test is a tuple, which is always

True- Change to

if True:

- Change to

- E402 Module level import not at top of file

- Move import to the top

- E722 Do not use bare

except- Change to

except Exception as e:

- Change to

Sometimes. when you fix an issue, you will get another. In this case I got another F401 'sys' imported but unused error, which I also fixed. You always need to run the linter again until all the errors have been resolved.

As mentioned, errors state what the problem is and give a rule number (e.g., F403) that you can look up on the Ruff Rules pages to get more information and suggestions on how to fix.

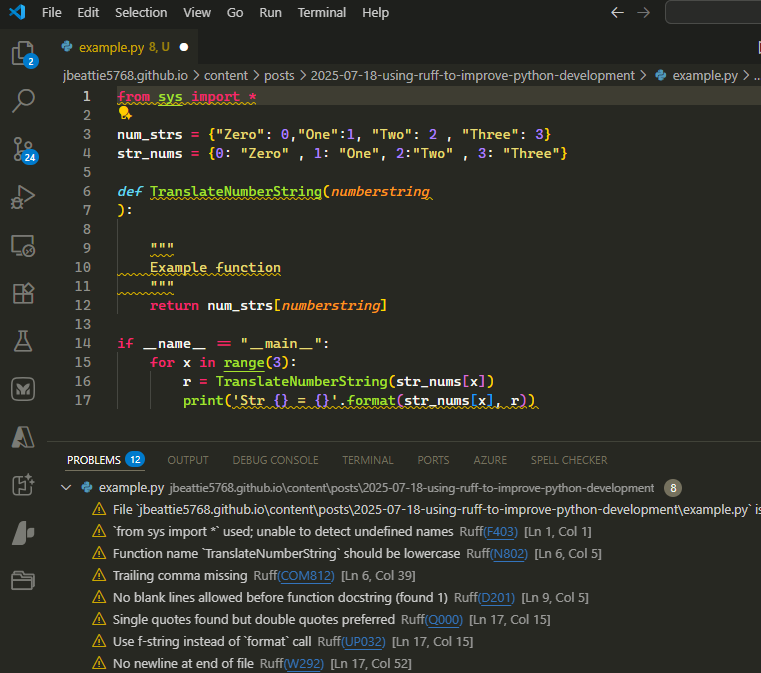

Note: When used within an IDE, hyperlinks are provided to quickly access information on the error.

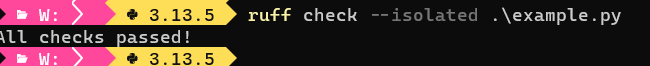

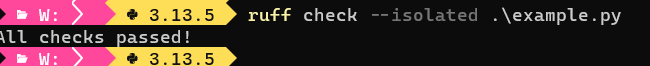

Now we have all checks passing:

ruff format .\example.py

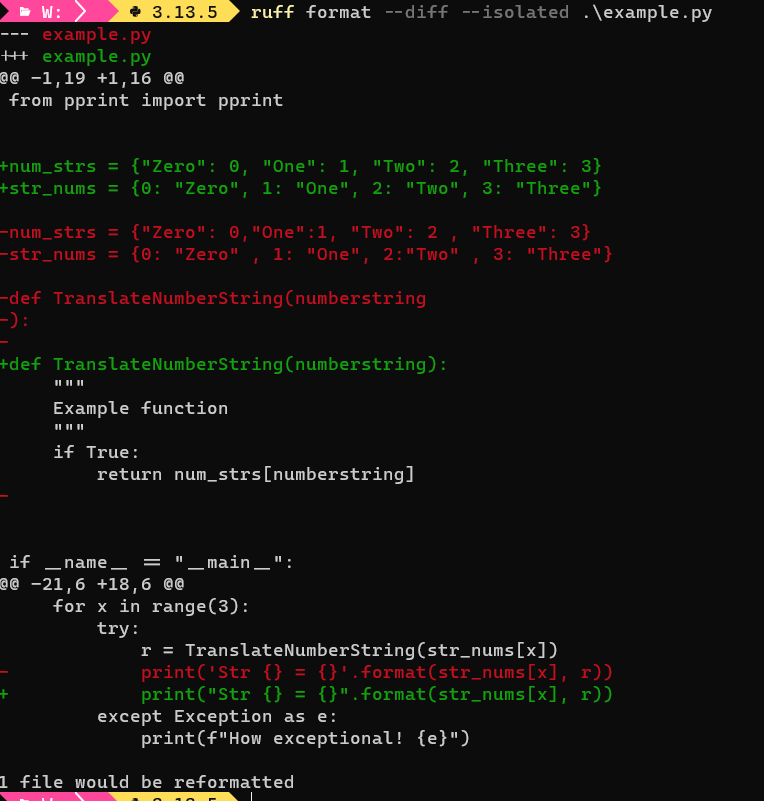

Before we format the remaining code, let’s take a look at what would be changed:

ruff format --diff .\example.py # Show what the changes 'would' be

Again I am using the --isolated option to use the default rules only.

let’s accept those changes and let Ruff format the code:

ruff format .\example.py # Apply the formatting changes

The final code now looks like this:

from pprint import pprint

num_strs = {"Zero": 0, "One": 1, "Two": 2, "Three": 3}

str_nums = {0: "Zero", 1: "One", 2: "Two", 3: "Three"}

def TranslateNumberString(numberstring):

"""

Example function

"""

if True:

return num_strs[numberstring]

if __name__ == "__main__":

pprint(num_strs)

pprint(str_nums)

for x in range(3):

try:

r = TranslateNumberString(str_nums[x])

print("Str {} = {}".format(str_nums[x], r))

except Exception as e:

print(f"How exceptional! {e}")

Although the code runs and does what was intended, there are still issues with this code. Linters and formatters are only there to help you, not to replace you!

Configuration

The rules used by Ruff are derived from multiple linters and formatters, and are configurable through hierarchical TOML files.

Whether Ruff is used as a linter, a formatter, or both, configuration follows the same methodology. Ruff will search for a configuration file in one of the following files .ruff.toml, ruff.toml or pyproject.toml in the closest directory and in that order of preference. Alternatively, you can specify any TOML file with the --config option.

It is common to include Ruff configuration in your project pyproject.toml file, as the Ruff configuration can be included in the projects version control.

The majority of projects using Ruff, as listed by Astral, use the projects existing pyproject.toml to store their Ruff configuration. For example:

FastApi using pyproject.toml

Pandas using pyproject.toml

Polars using pyproject.toml

As an aside, SCiPy has renamed their Ruff config file

lint.tomland explicitly referenced it in calling Ruff with the--configoption.

SciPylint.toml

SciPy calling Ruff with the--configoption

There is no reason not to have a separate ruff.toml in your project directory.

That’s all well and good, but what if we don’t have a project, but still want to check certain files on the command line. We have four options:

- Add a

pyproject.tomlto the directory - Add a

ruff.tomlto the directory - Use the

--configoption and point to an existingruff.tomllocated elsewhere - Have a default global

ruff.tomlthat will be used if no other configuration file is located.

For me, option four is preferred for the way I work (although I am trying to use pyproject.toml more often, even for sandbox directories). I now have a default ruff.toml in my Windows home directory and a symbolic link to the Ruff directory:

# Needs to be run as *PowerShell Admin (only Admin can create links)

# Use '-Force' in case '\AppData\Roaming\Ruff' dir has not been created

New-Item -ItemType SymbolicLink -Force -Path "$env:USERPROFILE\AppData\Roaming\Ruff\ruff.toml" -Target "$env:USERPROFILE\ruff.toml"

In my opinion, Ruff is a little lacking in not allowing a home directory default or fallback configuration file. Instead it has its file discovery, one of which is the ${config_dir}/ruff/ directory. For Windows, the $(config_dir) is equivalent to %userprofile%\AppData\Roaming, and if there is a pyproject.toml or ruff.toml located in the associated Ruff directory, that TOML will be used if no local config file is found.

Rules

Ruff rules are based on codes, [Letter Prefix][Number Code], e.g., F841.

The letter prefix indicates groups that are the source of the rule. This becomes more obvious when you look at the online Rules Documentation.

Additionally, there are Settings which work alongside rules and define some rule parameters. For example, E501 is “line too long”, which has a default of 88, but the setting line-length allows you to define the length after which this rule will be triggered, e.g.,:

# pyproject.toml

[tool.ruff]

line-length = 120 # Allow lines to be as long as 120.

The best way to start with your Ruff configuration is to add all rules, or the default set of group rules, and remove rules as they annoy you:

# pyproject.toml

[tool.ruff.lint]

select = ["ALL"]

# pyproject.toml

[tool.ruff.lint]

# RUFF DEFAULTS

select = [

"F", # pyflakes – detects syntax errors and basic mistakes

"E4", # pycodestyle errors (part of E group)

"E7", # pycodestyle E7xx errors (naming, etc.)

"E9", # pycodestyle E9xx errors (syntax)

]

I have opted to add all rules and remove them as they annoy me. Defining "ALL" will at least mean that if any new rules are implemented, I will not miss the chance for those rules to annoy me.

# ruff.toml

# Settings

line-length = 120 # To keep aligned with .editorconfig

[format]

line-ending = "lf" # Use `\n` line endings

[lint]

select = ["ALL"]

ignore = [

"ANN", # flake8-annotations - MyPy is checking annotations

"S311", # flake8-bandit - cryptographically weak `random` used

"RET504", # flake8-return - unnecessary assignment before `return` statement

"D200", # pydocstyle - unnecessary multiline docstring

"D203", # pydocstyle - blank line before class docstring

"D212", # pydocstyle - docstring not on 1st line after opening quotes

"D400", # pydocstyle - missing trailing period in docstring

"D401", # pydocstyle - docstring first lines are not in an imperative mood

"D415", # pydocstyle - missing terminal punctuation (.,? or !)

# "PERF401" # Perflint - `for` loop can be replaced by list comprehension

# Consider removing these for projects/publication

"D1", # pydocstyle - missing docstring

"ERA001", # eradicate - found commented out code

"T201", # flake8-print - `print` found

"T203", # flake8-print - `pprint` found

]

[lint.per-file-ignores]

"tests/*.py" = ["S101"] # Use of `assert` detected

"test_*.py" = ["S101"] #

At the moment, this gets me through most of my scripts and is small enough to transfer to a pyproject.toml if needed.

There are plenty of GitHub projects using Ruff to show configuration examples.

Integrating Ruff into your workflow

CLI

See Basic CLI Usage.

IDE

As usual, Astral have done a great job with the Editors Setup Documentation.

I use VSCode and it is pretty simple:

-

Install and enable the Ruff Extension from the Visual Studio Marketplace.

-

Configure Ruff to be the default formatter and take action on save:

// Editor: Python Specific Settings "[python]": { "editor.defaultFormatter": "charliermarsh.ruff", "editor.formatOnSave": true, "editor.codeActionsOnSave": { // "source.fixAll": "explicit", "source.organizeImports": "explicit", }, },

You can include and exclude rules in the settings.json, but they are better placed in a project TOML file.

Once installed in VSCode, Ruff will automatically run when you open or edit a Python file.

You can click the rule in the Problems panel and be taken to a webpage explaining that rule. You can right-click the issue and select auto-fix, ignore, etc. All good stuff.

Pre-Commit

If you have pre-commit set up for your project, you can add the ruff-pre-commit to it as well.

# .pre-commit-config.yaml

repos:

- repo: https://github.com/astral-sh/ruff-pre-commit

# Ruff version.

rev: v0.12.10

hooks:

# Run the linter.

- id: ruff-check

# args: [ --fix ]

# Run the formatter.

- id: ruff-format

GitHub Actions

If you have GitHub Actions set up for your project, you can add a ruff-action to it as well. Either as a file:

# ruff.yml

name: Ruff

on: [ push, pull_request ]

jobs:

ruff:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v6

- uses: astral-sh/ruff-action@v3

…or add the following to your CI/CD workflow:

- uses: astral-sh/ruff-action@v3

Tips

-

Which config file is it using now?

-

CLI: add

--verboseand it will one of the first things printed -

VSCode: Add the following to your workspace settings:

"ruff.logLevel": "debug", "ruff.logFile": "c:/temp/ruff.log",- The log will show which TOML is being used (there may be more than one referenced in the log)

-

-

How do I get Ruff to ignore only this line?

- Sometimes not everything is fixable, or needs to be fixed

- Add

# noqa: <rule>to the line, e.g.,# noqa: D201, and it will get ignored

-

I like Black; can I use it as well as Ruff?

-

CLI: No problem. They are in different sections of the

pyproject.tomlfile- Important: Make sure the

line-lengthsetting is the same for both, or they will continually conflict - Run

ruff check example.pyandblack example.pyas you normally would on the CLI

- Important: Make sure the

-

VSCode: You can set Black to be the Formatter and Ruff to be the Linter in the

settings.jsonfile# settings.json "ruff.lint.enable": true, ... ... "python.formatting.provider": "black", ... ...

-

-

I do not want it to format a section of code

- Add the

# fmt: off/# fmt: onpairing around the code you do not want formatted. These need to be on separate lines. - For single lines, use

# fmt: skipafter the command to be left unchanged. - Examples for both options:

# fmt: off for status in [(-1, -1), (-1, 0), (-1, 1), ( 0, -1), ( 0, 1), # show (row,col) offset ( 1, -1), ( 1, 0), ( 1, 1)]: # fmt: on print(f"Status: {status}") # Ruff Formatting would change this to be: for status in [(-1, -1), (-1, 0), (-1, 1), (0, -1), (0, 1), (1, -1), (1, 0), (1, 1)]: print(f"Status: {status}") import pdb; pdb.set_trace() # fmt: skip # Ruff formatting would change this to be: import pdb pdb.set_trace() - Add the

Conclusion

Improving your code should be as painless as possible. The coverage and speed of Ruff help greatly, but I think the biggest benefit I have seen is that I am learning from it.

The speed helps with the feedback loop.

The use of TOML files is simple and easy to add or remove rules.

Do not get bogged down with it; instead embrace it as you move forward.

Further Reading

- Ruff Documentation

- Other Python code analysis tools that can give early warnings about certain aspects of your code, such as a complexity metric:

Edits to this Post

- 05 Jan 2026: Added “I do not want it to format a section of code” entry to Tips section.

- 05 Jan 2026: Added banner image and updated some formatting.

- 12 Jan 2026: MD Linting and AI Spelling, Grammar checks.